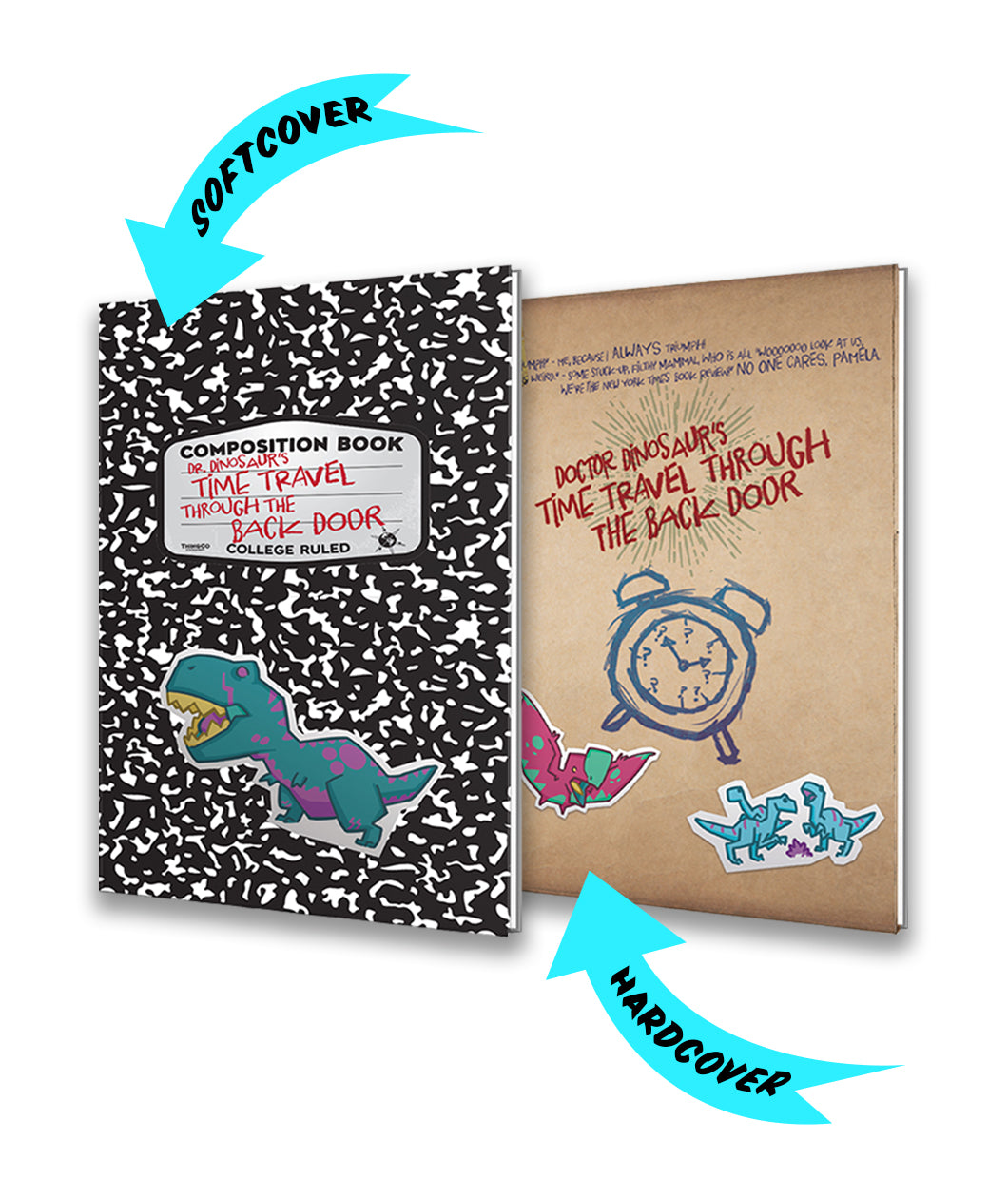

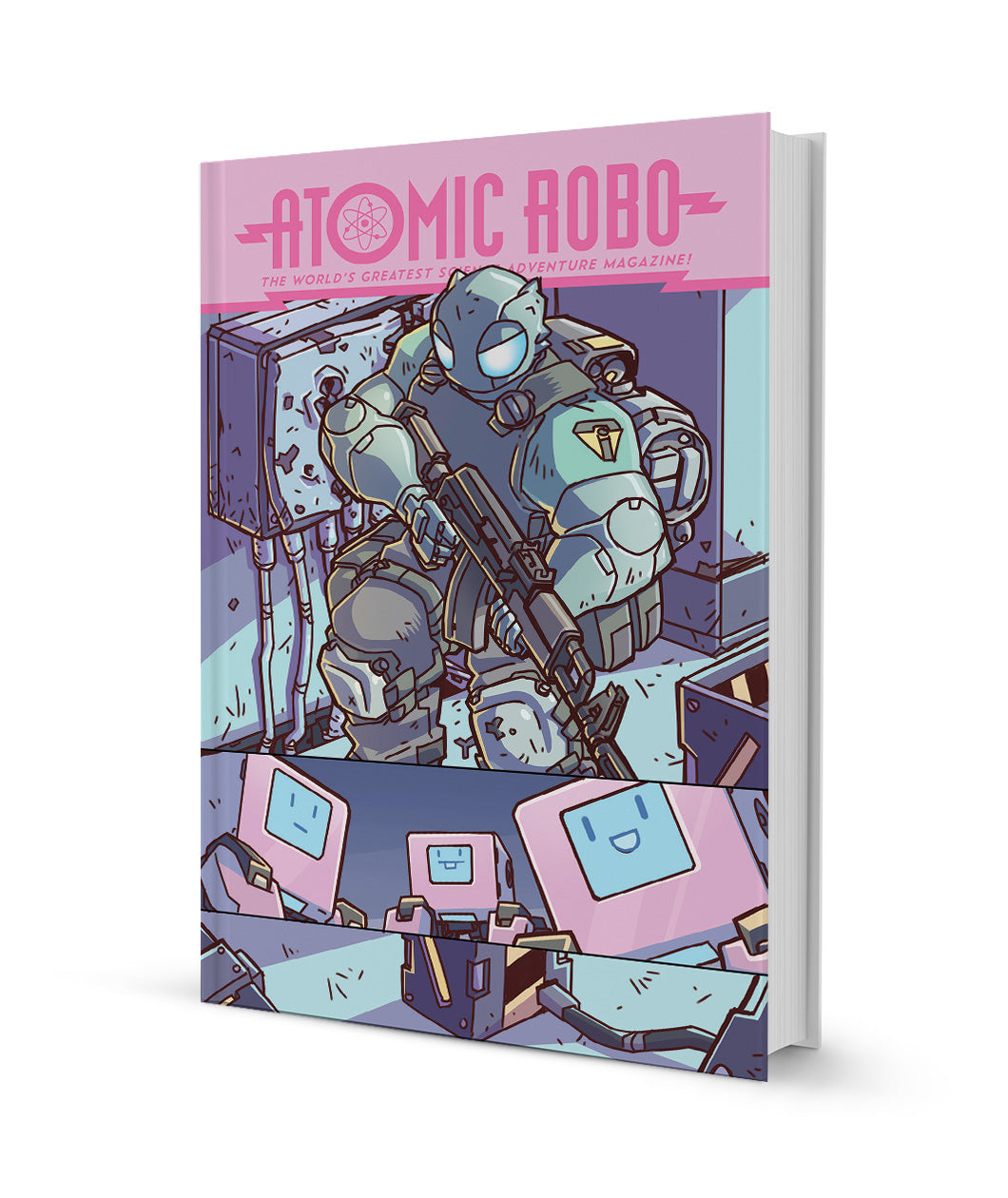

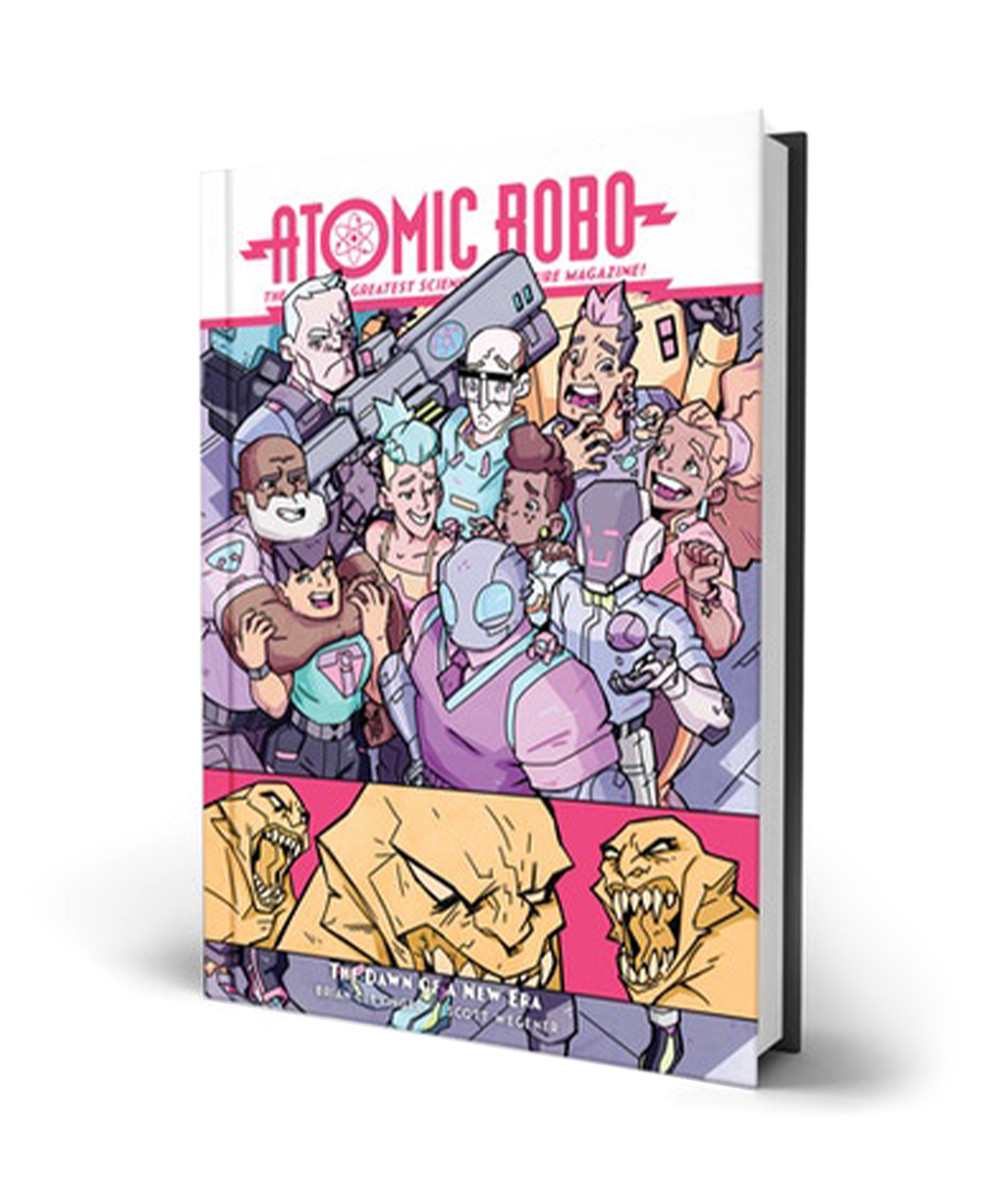

Like I said at the start of this li'l blogging project, I do Way Too Much Research for ATOMIC ROBO.

This does not affect you, the reader, because I wisely only include about 5% of it on the page. That doesn’t mean the other 95% is wasted — hey, that’s Rule Three from the previous section, wow! — because I can’t know which 5% belongs on the book without the other 95%.

And, hey, joke’s on all of you, I’m only writing the comics to get paid for reading history books anyway! HAW HAW.

But research can be tricky. The two most common research blunders I see are...

(1) Researching instead of writing.

(2) Writing the research instead of the story.

These are bad habits that can get in the way of writing and I’ve certainly never been guilty of either of them, nope, trust me, don’t look into it, moving on.

Today we'll focus on that first one: Researching instead of writing.

Look, writing is hard. I mean, it’s not hard like competing at the Olympics is hard. Or how working in retail is hard. It’s hard in a weird and nebulous way because at least with the Olympics or retail there’s an absolute goal to work toward, from having the best time humanly possible to the least worst time humanly possible. And, generally, there are objective markers that let you know when you’re doing it wrong at every step of the way.

Writing is more like competing in the Olympics only you never tried out, and the competition runs 24/7 for some reason, and no one will tell you when it’s your turn, or what you’ll be competing in when you get there, or where the competition is but you’ll be fired if you aren’t there on time, but don't worry because you'll also be fired if the judge is in a bad mood because of something completely unrelated that happened to them at lunch so your actual performance is meaningless either way, except when it isn't, and fuck you for trying.

Sounds kinda stressful right? Like, if you had to live and work under that cloud of confusion you’d be exhausted all the time! Well, that's the way writing is hard. Because it’s baffling. You’re never sure where you’re going with it, you’re never sure when you’ll be done, you’re never sure if you did it right when you are done, you’re never sure if you’re done, you’re never sure if you should scrap the whole thing to start over, and you’re never sure if it was worth doing at all.

It’s why you read stuff like this to try to figure out what the hell is going on.

You know what’s way easier than writing? Doing something that feels like writing without doing all the hard parts! Something like research!

You need to do some research, no one's arguing against that. But it's real easy to find yourself doing Way Too Much Research! This is most often characterized as Way Too Much Worldbuilding.

Read an article? Research! Took some notes? Research! Went to the library? You better believe that’s research!

And researching is (technically) working on your story, and you have to do it before you write, so technically it’s fine to do research and it’s totally not ever about putting off all that writing that's so god damn baffling and terrifying NO SIREEBOB.

Okay, but research doesn’t add a single page to your current draft. Writing is writing. Research is research.

Now, I’m not saying don’t do research. I’ve been off-and-on writing a story that takes place in 16th century China and it would be the worst idea to go into that blind. Research is integral to getting this thing written! Definitely do your research!

But there’s a thin line between doing research that's necessary and doing research to feel like you’re writing. This usually — not always, but usually — takes the form of worldbuilding.

I’ve railed against excessive worldbuilding before, so let me make this clear: WORLDBUILDING GOOD. It’s just that the right amount of it isn’t far from too much of it. And it’s hard to define where exactly the difference between them is because how much is too much depends on the type of research being done and the type of project it’s for, who you are, the audience’s expectations, etc. We can’t work out an objective system that considers all the variables, so let’s try this instead.

Remember that you’ll never actually do enough research. It's a trap. You cannot possibly do "enough." Especially with regard to something like historical fiction. Even if you lived through the time and in the place of the story, you’re going to get something about it wrong.

It’s fine! Honestly.

I mean, don’t get the date of the Moon Landing wrong — unless you’re doing alternative history in which case 1899 is a perfectly legit date for landing on the Moon — but it’s okay to get some stuff wrong! You’re not writing a documentary, you’re not writing a dissertation, you’re writing a story. You need only to invoke a sense of the era, not a perfect facsimile of it.

You’re never going to get the voice of the era just right, you’re never going to get the slang of that place just right, and you’re going to screw up the price of milk. It’s fine! I promise you.

The alchemy of writing a story for someone else to read is an inherently fuzzy process. Consider that no two people are going to have the same experience of the same text. They will even remember the exact same scene in completely incompatible ways! Every reader carries their own version of the story in their own minds with their own vision of what happened and how. Even in comics where there are literal actual images on each and every page! This fuzziness isn’t something you can overcome by researching yourself down to the precise location and velocity of each individual main character and their lineages across a dozen previous generations. Readers understand and expect some fuzziness in fiction because everything they’ve ever read was built out of that fuzziness. You can use it to your advantage. Here’s one way: hide stuff in it! You can frame information to de-emphasize or to hand wave away incidental details that would require hours and hours of digging and researching to ferret out.